Image 1 of 2

Image 1 of 2

Image 2 of 2

Image 2 of 2

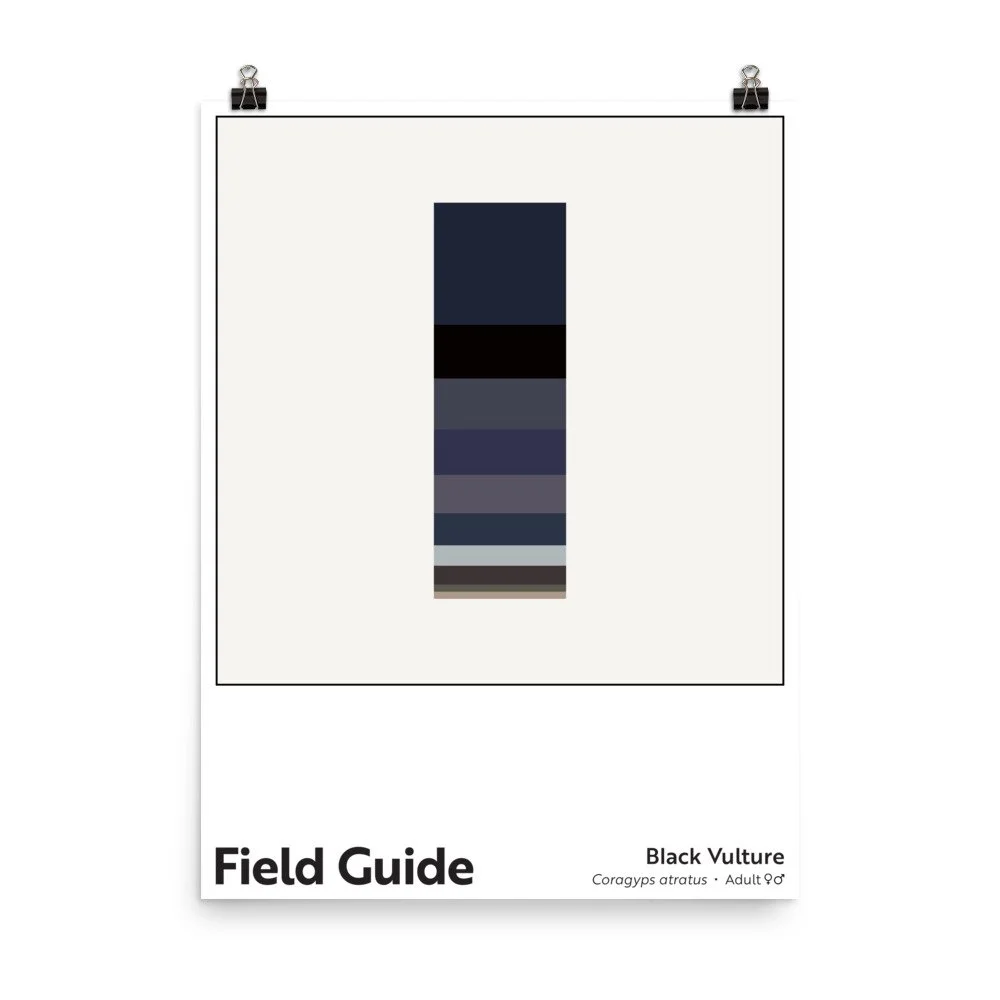

Field Guide : Black Vulture

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

My 86-year-old father yells at black vultures. That might sound like my family’s version of “Old Man Yells At Cloud,” but my dad shouts with good reason. Unlike turkey vultures, black vultures seem to have a predilection for property destruction. When the birds perch atop his home on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, they don’t just rest and relieve themselves; they also tear at the shingling. Hearing their efforts above, my dad heads outside as fast as he can to shout and wave his arms all about. When those antics don’t work – and they rarely do – he heads inside, grabs his shotgun, and returns to fire a round or two skyward, startling the birds and usually causing them to relocate. Alas, they often return within the hour. Researchers aren’t quite sure why black vultures tear at shingles, but the birds also target caulking (especially around house and vehicle windows) and other vinyl and plastic compounds.

The black vulture is aggressive and opportunistic in other ways, too. It has a smaller olfactory bulb than its close relative the turkey vulture, so black vultures, which generally feed in groups (unlike their more solitary cousin), often follow turkey vultures to carrion, then gang up on the larger bird to move it off the food that they then lay claim to. They fight within their own kind, as well, pecking, grappling, biting, and wing striking, but researchers note that black vultures generally don’t fight with their immediate kin.

The black vulture’s range is not quite as extensive as the turkey vulture’s….yet. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the black vulture has expanded its range “substantially since the 1920s.” Before that time, it was “unknown in the Northeast, or even as far north as Virginia.” Today, with large numbers of the birds attempting to roost on my father’s Virginia house, that clearly isn’t the case. Likewise, in South America, the species has expanded its range. Presently, healthy black vulture populations extend from New Mexico in the west and Vermont in the east south to southern Chile and Argentina. They are thriving, in no small part, because of our human footprint; garbage dumps and roadkill supply new food sources and, because black vultures are so aggressive, the expansion of livestock husbandry, especially in South America, offers additional predation opportunities, as the birds will target newborn cattle, sheep, goats, and horses.

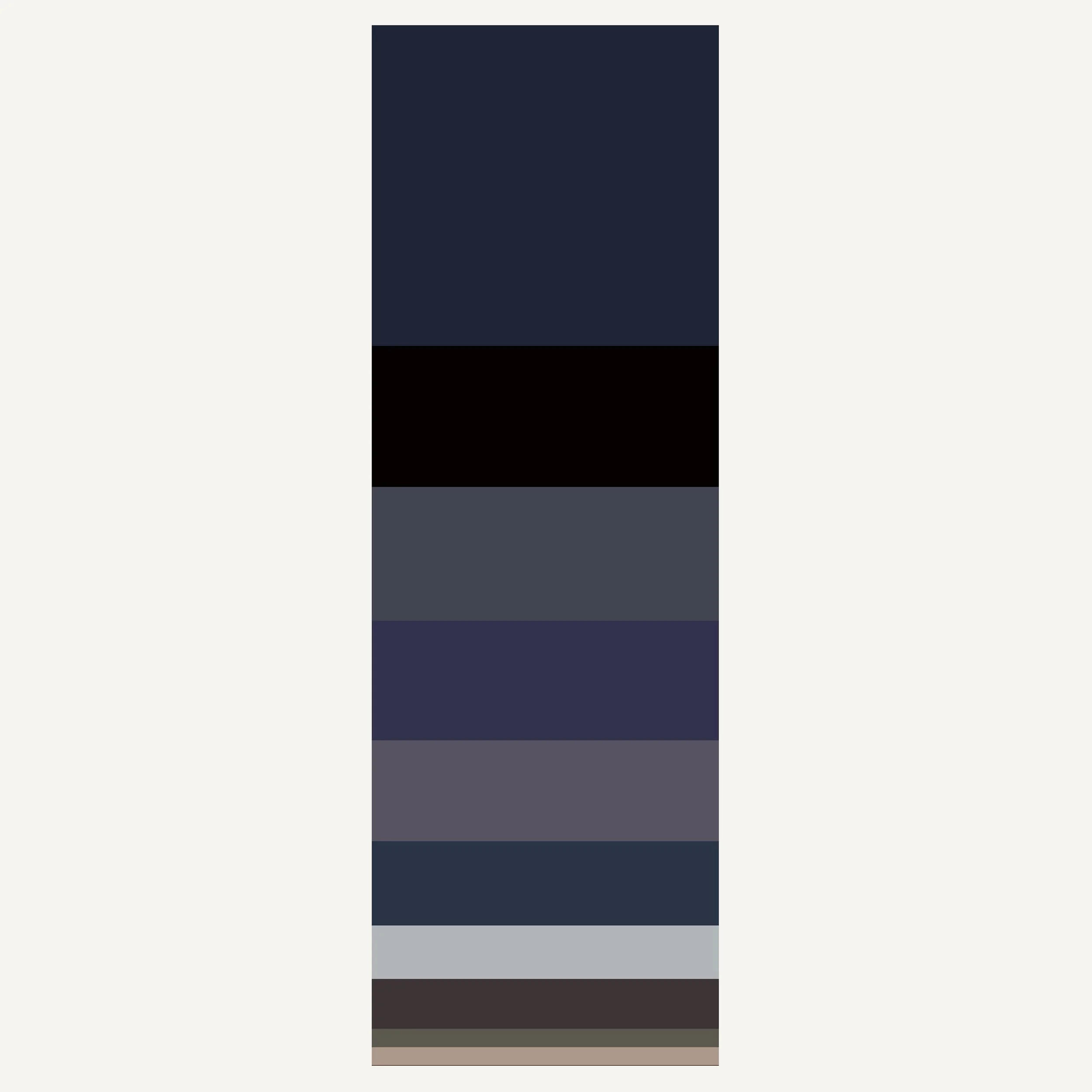

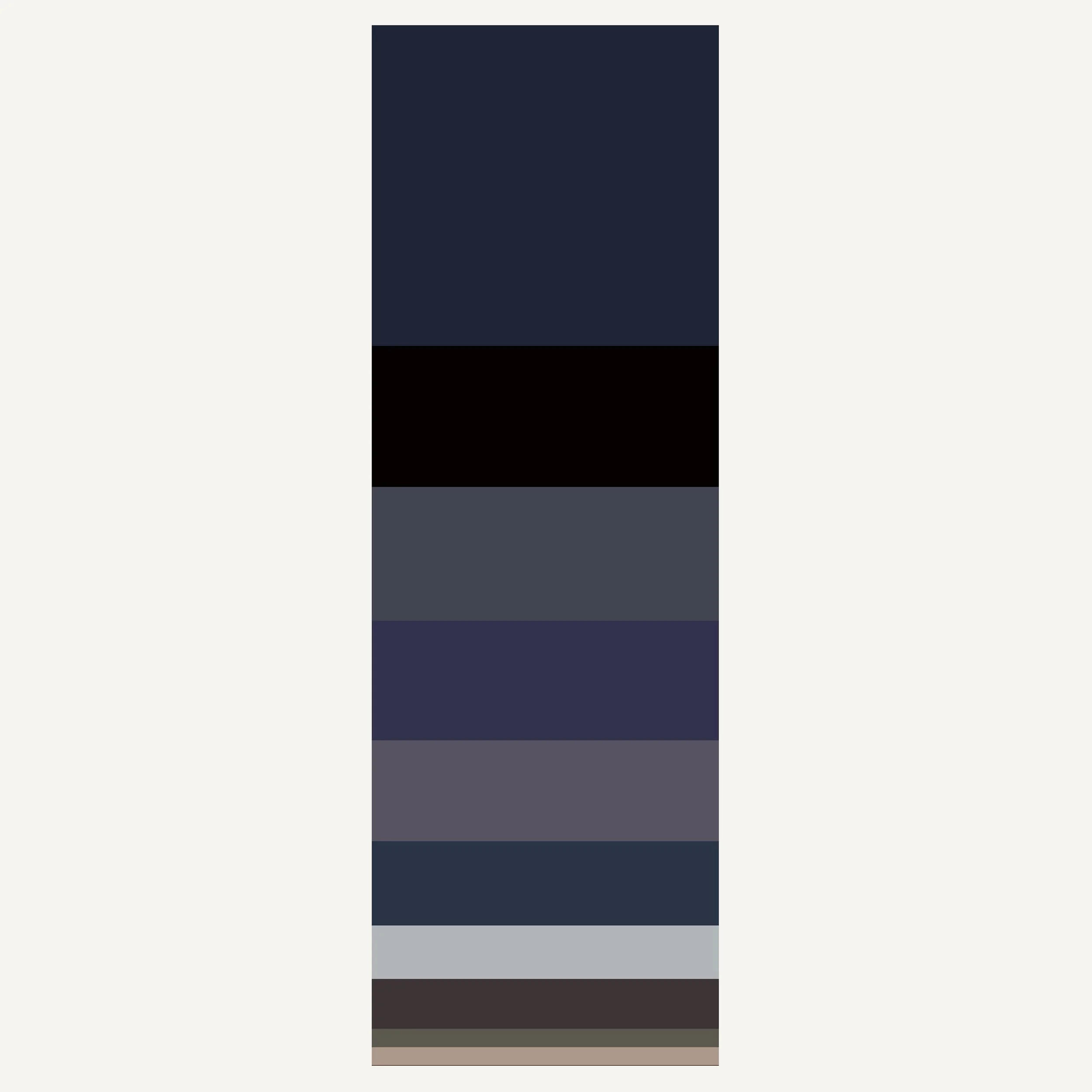

Although black vultures are generally described as “entirely black,” that “black” isn’t mostly, well, black. Close observation shows that much of the raptor’s dark plumage is a midnight blue, gunmetal grey, and even violet. And the bird’s legs and head add in silver, some browns, and a wee bit of maroon (mostly drawn from the bird’s iris). Overall, I think of the bird as more charcoal than black.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

My 86-year-old father yells at black vultures. That might sound like my family’s version of “Old Man Yells At Cloud,” but my dad shouts with good reason. Unlike turkey vultures, black vultures seem to have a predilection for property destruction. When the birds perch atop his home on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, they don’t just rest and relieve themselves; they also tear at the shingling. Hearing their efforts above, my dad heads outside as fast as he can to shout and wave his arms all about. When those antics don’t work – and they rarely do – he heads inside, grabs his shotgun, and returns to fire a round or two skyward, startling the birds and usually causing them to relocate. Alas, they often return within the hour. Researchers aren’t quite sure why black vultures tear at shingles, but the birds also target caulking (especially around house and vehicle windows) and other vinyl and plastic compounds.

The black vulture is aggressive and opportunistic in other ways, too. It has a smaller olfactory bulb than its close relative the turkey vulture, so black vultures, which generally feed in groups (unlike their more solitary cousin), often follow turkey vultures to carrion, then gang up on the larger bird to move it off the food that they then lay claim to. They fight within their own kind, as well, pecking, grappling, biting, and wing striking, but researchers note that black vultures generally don’t fight with their immediate kin.

The black vulture’s range is not quite as extensive as the turkey vulture’s….yet. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the black vulture has expanded its range “substantially since the 1920s.” Before that time, it was “unknown in the Northeast, or even as far north as Virginia.” Today, with large numbers of the birds attempting to roost on my father’s Virginia house, that clearly isn’t the case. Likewise, in South America, the species has expanded its range. Presently, healthy black vulture populations extend from New Mexico in the west and Vermont in the east south to southern Chile and Argentina. They are thriving, in no small part, because of our human footprint; garbage dumps and roadkill supply new food sources and, because black vultures are so aggressive, the expansion of livestock husbandry, especially in South America, offers additional predation opportunities, as the birds will target newborn cattle, sheep, goats, and horses.

Although black vultures are generally described as “entirely black,” that “black” isn’t mostly, well, black. Close observation shows that much of the raptor’s dark plumage is a midnight blue, gunmetal grey, and even violet. And the bird’s legs and head add in silver, some browns, and a wee bit of maroon (mostly drawn from the bird’s iris). Overall, I think of the bird as more charcoal than black.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.