Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

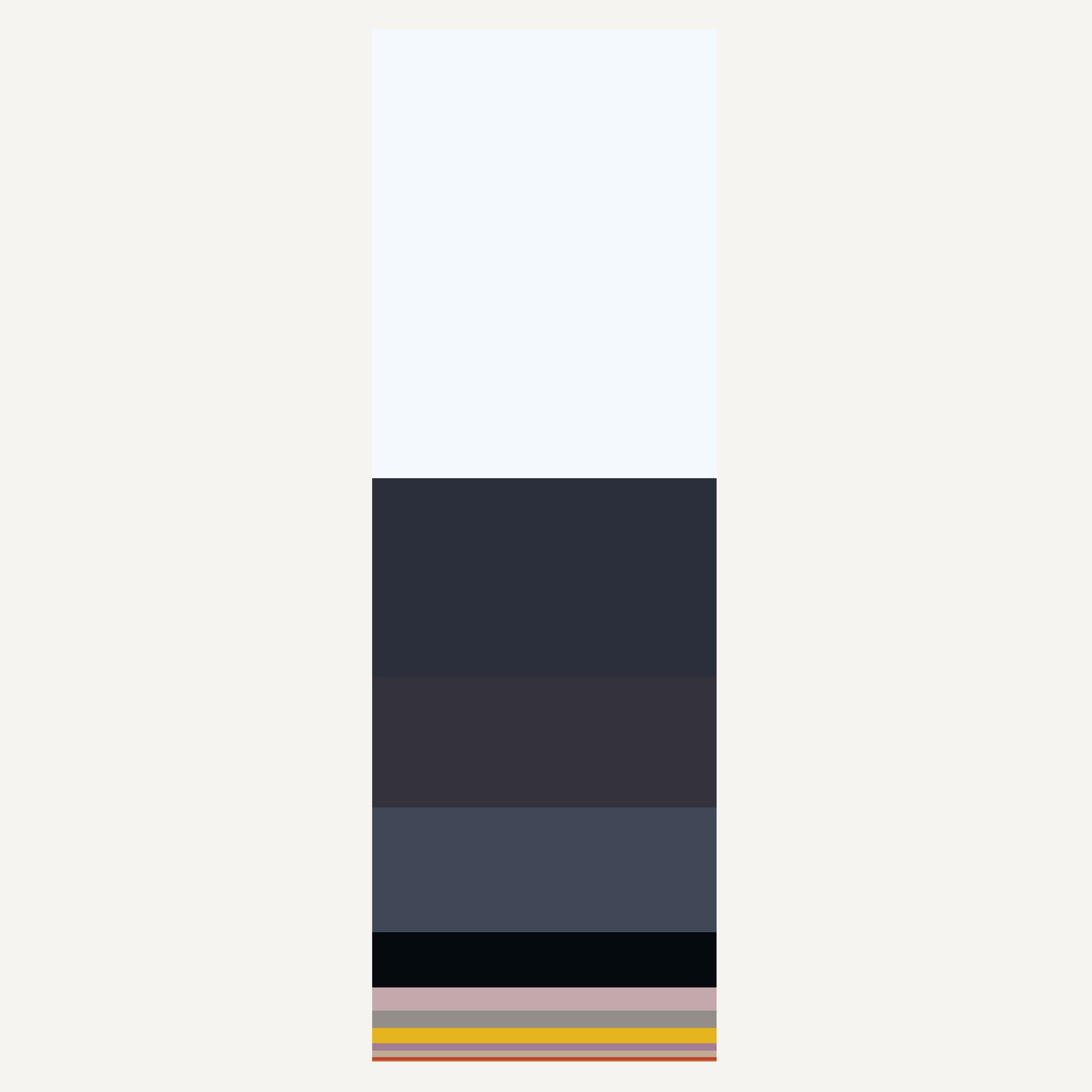

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

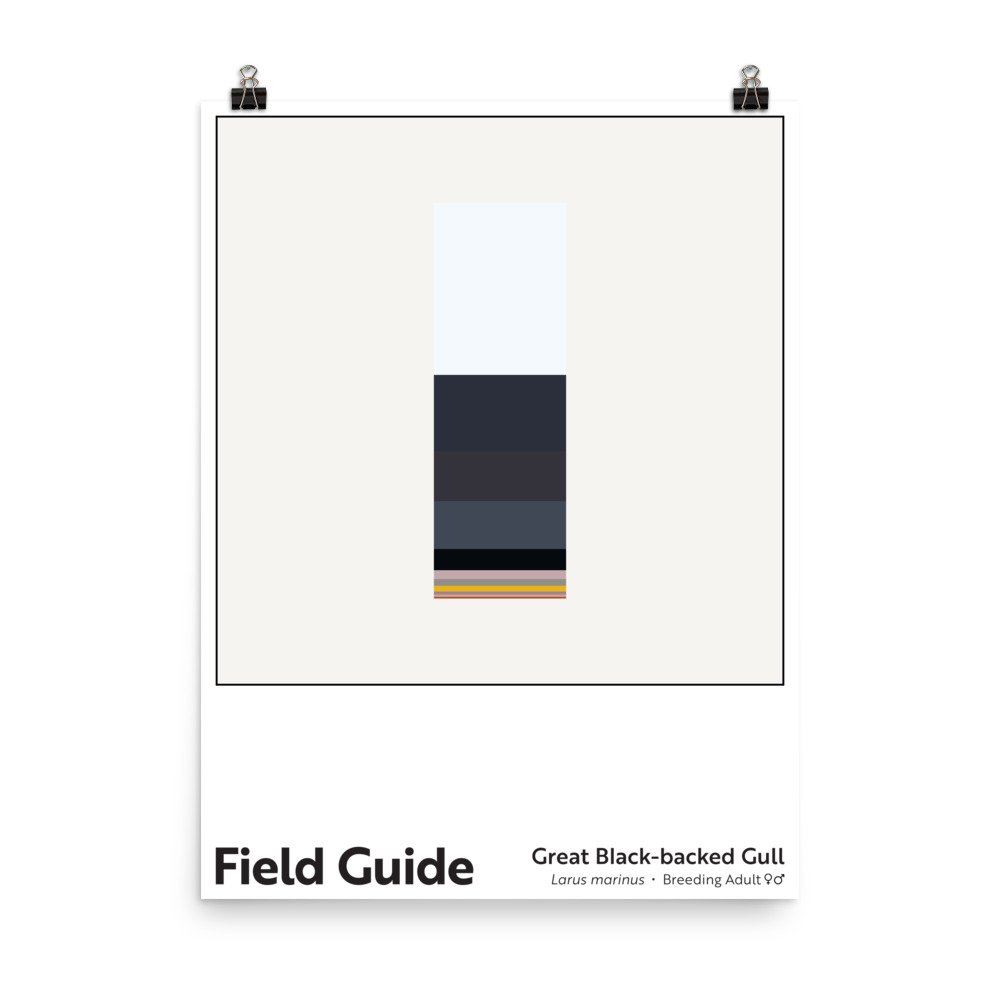

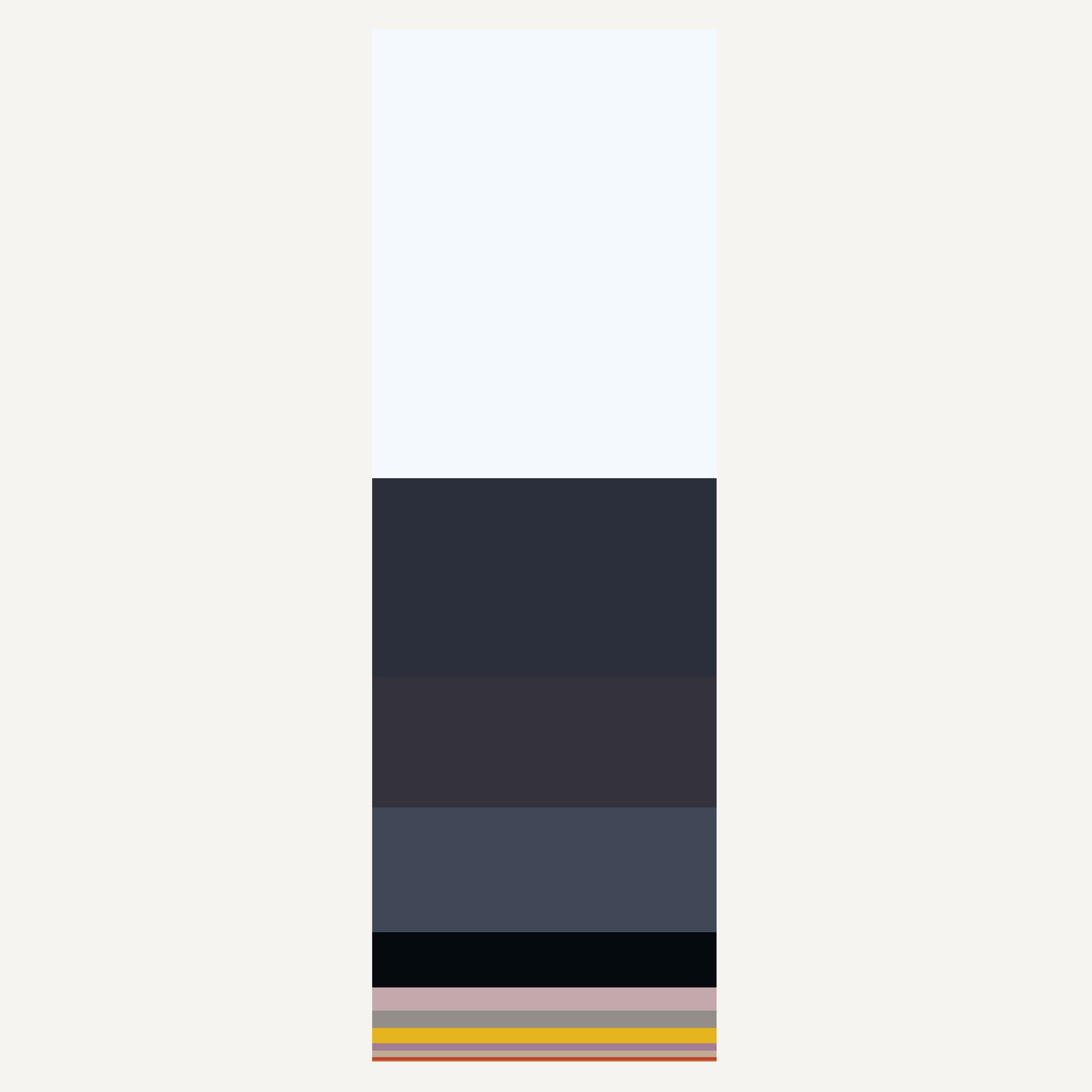

Field Guide : Great Black-backed Gull

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The great black-backed gull is the largest member of the gull family. It’s so big that soaring great black-backed gulls are often misidentified as bald eagles – a mistake no bird nerd would make, but an understandable one for most folks. Like eagles, though, great black-backed gulls have a fearsome reputation. I’ve heard them described as ruthless, although that’s just a judgy way of acknowledging their supreme and aggressive predatory behavior. One of the bird’s colloquial names is coffin-bearer, a reference to its outfit, which calls to mind a person in a dark suit and white shirt, but I tend to associate that nickname with the death it deals; the coffin it bears is its always-wanting stomach.

Like most gull species, the great black-backed diet is broad. They subsist mostly on fish, crustaceans, and echinoderms (marine invertebrates such as sea stars), but they’ll never turn their beak up at scavenging, whether it’s the crust of a sandwich dropped on a beach or a potato chip bonanza at the local dump. None of those menu items led to their disrepute, however. Rather, it’s the great black-backed gull’s propensity to attack and eat smaller seabirds such as puffins, grebes, small ducks, terns, and other, smaller gulls, as well as its regular bullying and theft of other birds’ meals – including eagles – that’s given rise to their reputation. (Hell, they’ve been documented stealing food from sharks!) Because they’re so highly predatory and known for hunting and killing other birds, the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology characterizes them as “behaving more like a raptor than a typical larid gull.” We humans always seem to be ambivalent about our fellow predators, simultaneously admiring and detesting them. I grew up thinking great black-backed gulls a scourge.

The conservation story of the great black-backed gull is compelling, in part because it’s so complicated. During the 19th century, the North American population of great black-backed gulls was almost wiped out due to feather hunters and egg harvesters. Fortunately, late 19th- and early 20th-century conservation measures helped save the imperiled gull from extinction or regional extirpation (along with many other bird species). In addition to those legal protections, great black-backed gulls benefited from the staggering amount of waste North Americans produced in the 20th century; all those growing landfills provide abundant scavenging opportunities. By the middle of the century, the great black-backed gull population in North America exceeded its former peak and its range was expanding south along the Atlantic coast. But this isn’t a straightforward conservation success story. As the gull’s population rebounded and its range stretched south, it took more and more of a toll on other bird species, especially its close relative the American herring gull (Larus smithsonianus) and, on some Atlantic islands, tern and puffin species. As a result, conservationists have intervened. On select islands, conservationists protect Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) and certain tern species by shooting, harassing, and/or poisoning the gulls to reduce or eliminate their breeding there. Similarly, major airports regularly shoot the gulls to reduce aircraft collisions – JFK International Airport has been doing so since 1991, and found that regular culling of great black-backed gulls reduced plane-bird collisions by at least 60%. So we’ve gone from a collapsing population to what may be too robust a population…or have we? There are now conflicting reports about the bird’s global population; some say it continues to increase globally, whereas others suggest the great black-backed gull population has experienced a 50% decline since 1975. I’m not sure what to think, but old attitudes die hard. When I saw a great black-backed gull fly by our boat during a recent trip to my home ground on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, my first thought was, “damned black back.”

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The great black-backed gull is the largest member of the gull family. It’s so big that soaring great black-backed gulls are often misidentified as bald eagles – a mistake no bird nerd would make, but an understandable one for most folks. Like eagles, though, great black-backed gulls have a fearsome reputation. I’ve heard them described as ruthless, although that’s just a judgy way of acknowledging their supreme and aggressive predatory behavior. One of the bird’s colloquial names is coffin-bearer, a reference to its outfit, which calls to mind a person in a dark suit and white shirt, but I tend to associate that nickname with the death it deals; the coffin it bears is its always-wanting stomach.

Like most gull species, the great black-backed diet is broad. They subsist mostly on fish, crustaceans, and echinoderms (marine invertebrates such as sea stars), but they’ll never turn their beak up at scavenging, whether it’s the crust of a sandwich dropped on a beach or a potato chip bonanza at the local dump. None of those menu items led to their disrepute, however. Rather, it’s the great black-backed gull’s propensity to attack and eat smaller seabirds such as puffins, grebes, small ducks, terns, and other, smaller gulls, as well as its regular bullying and theft of other birds’ meals – including eagles – that’s given rise to their reputation. (Hell, they’ve been documented stealing food from sharks!) Because they’re so highly predatory and known for hunting and killing other birds, the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology characterizes them as “behaving more like a raptor than a typical larid gull.” We humans always seem to be ambivalent about our fellow predators, simultaneously admiring and detesting them. I grew up thinking great black-backed gulls a scourge.

The conservation story of the great black-backed gull is compelling, in part because it’s so complicated. During the 19th century, the North American population of great black-backed gulls was almost wiped out due to feather hunters and egg harvesters. Fortunately, late 19th- and early 20th-century conservation measures helped save the imperiled gull from extinction or regional extirpation (along with many other bird species). In addition to those legal protections, great black-backed gulls benefited from the staggering amount of waste North Americans produced in the 20th century; all those growing landfills provide abundant scavenging opportunities. By the middle of the century, the great black-backed gull population in North America exceeded its former peak and its range was expanding south along the Atlantic coast. But this isn’t a straightforward conservation success story. As the gull’s population rebounded and its range stretched south, it took more and more of a toll on other bird species, especially its close relative the American herring gull (Larus smithsonianus) and, on some Atlantic islands, tern and puffin species. As a result, conservationists have intervened. On select islands, conservationists protect Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) and certain tern species by shooting, harassing, and/or poisoning the gulls to reduce or eliminate their breeding there. Similarly, major airports regularly shoot the gulls to reduce aircraft collisions – JFK International Airport has been doing so since 1991, and found that regular culling of great black-backed gulls reduced plane-bird collisions by at least 60%. So we’ve gone from a collapsing population to what may be too robust a population…or have we? There are now conflicting reports about the bird’s global population; some say it continues to increase globally, whereas others suggest the great black-backed gull population has experienced a 50% decline since 1975. I’m not sure what to think, but old attitudes die hard. When I saw a great black-backed gull fly by our boat during a recent trip to my home ground on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, my first thought was, “damned black back.”

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.