Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Field Guide : Great Egret

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The great egret is our largest white heron. The “our” in that statement is cosmopolitan, like the bird itself; the species is found on five of the seven continents (absent only in Australia and Antartica). Keen readers may wonder why I called this largest of egrets a heron. It surprises many folks, but all egrets are herons. In fact, the Ardea genus to which the great egret belongs contains 6 species with “egret” common names and 10 species with “heron” common names, including the great blue heron (Ardea herodias). There’s no significant biological boundary between herons and egrets; perhaps it’s easiest to think of it this way – “egret” is the common name generally assigned to the whiter herons.

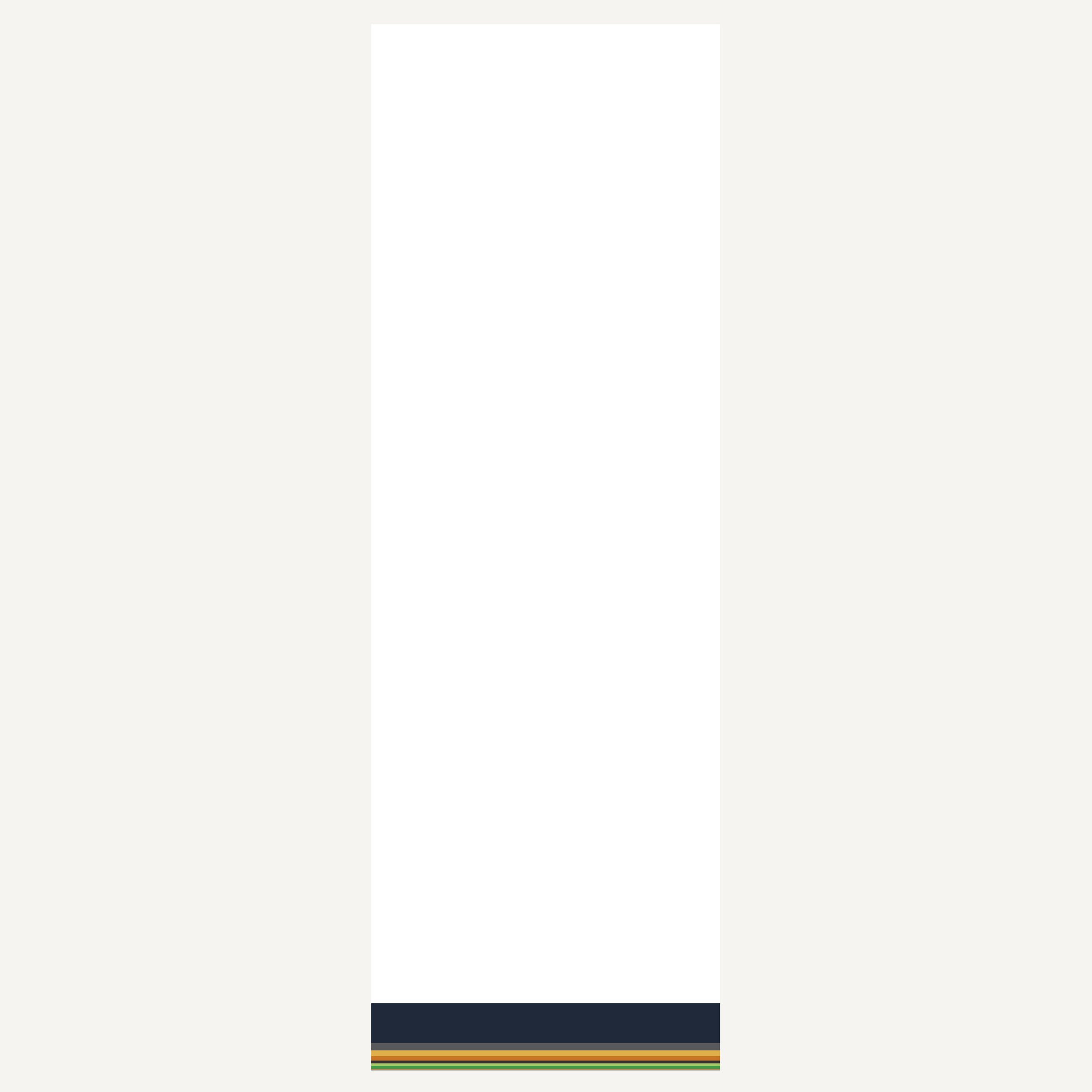

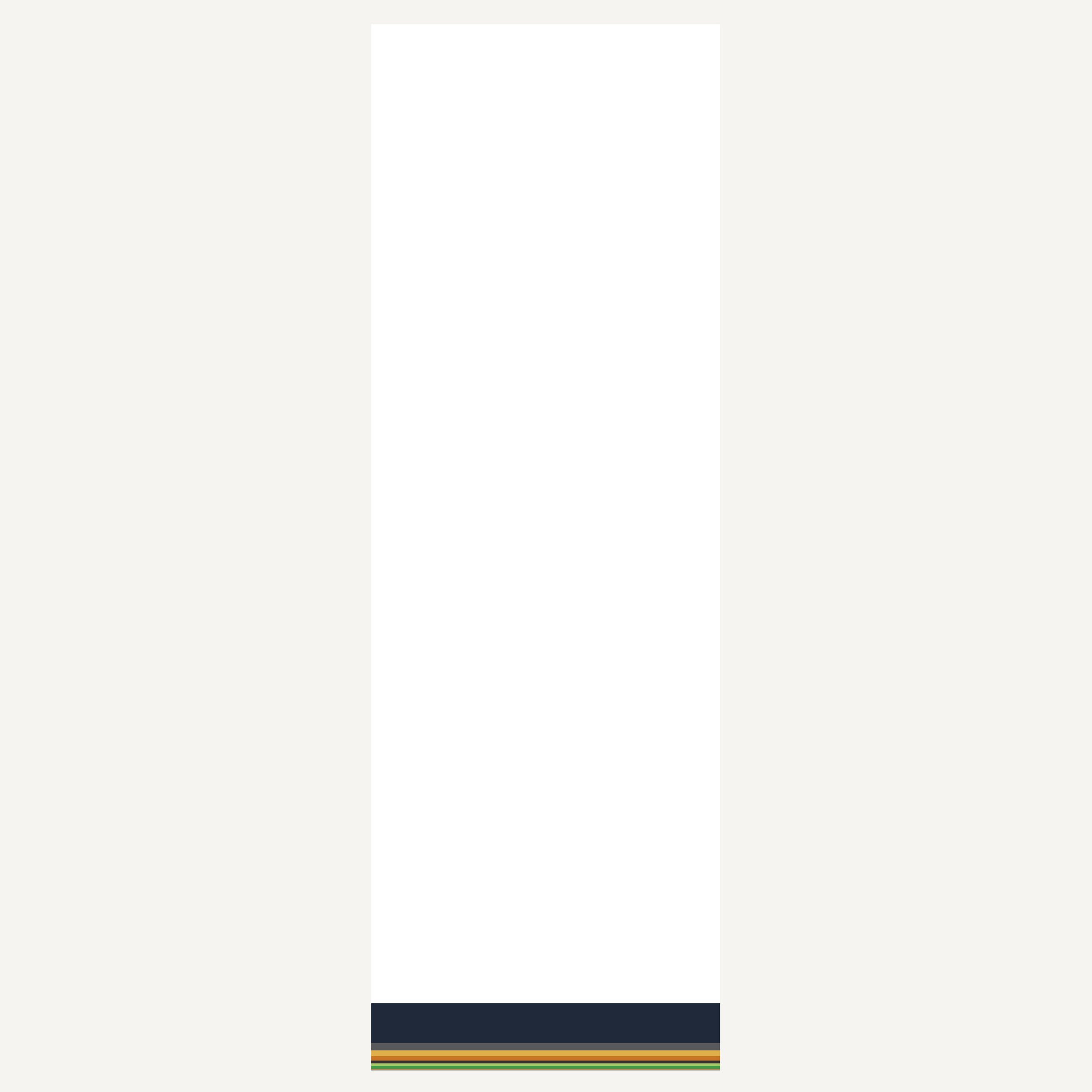

Great egrets are found near water, whether fresh or salt, and most closely associated with wetlands. During the breeding season, they get all gussied up. Each egret, both males and females, grow long plumes called aigrettes (from the French for “egret”), which cascade down its back. The egret’s unfeathered parts also become more intensely colored; the flesh around the eyes and between the eyes and bill turns emerald and pistachio, and the bill itself becomes more saturated carrot and saffron. The aforementioned aigrettes help egrets attract a mate, but they also caught the eye of late-19th century Europeans, who desired the plumes for ladies’ hats. As a result, great egrets were one of a number of “white heron” species that were exploited and over-hunted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 1880s, demand was so high that the plumes sold for twice the price of gold! Fortunately, some hunter-conservationists of the day noticed that populations of waterbirds were reeling from the combination of habitat loss and the myopic, kill-them-all-for-today’s-pay-day approach of market hunters, and they resolved to take action. The reforms they managed to pass represent major victories for the then-nascent conservation movement and, importantly, allowed many waterbird and shorebird populations to recover.

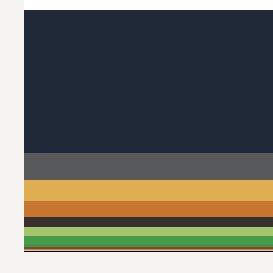

This color column is based on A. a. egretta, the subspecies that occurs in the Americas.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The great egret is our largest white heron. The “our” in that statement is cosmopolitan, like the bird itself; the species is found on five of the seven continents (absent only in Australia and Antartica). Keen readers may wonder why I called this largest of egrets a heron. It surprises many folks, but all egrets are herons. In fact, the Ardea genus to which the great egret belongs contains 6 species with “egret” common names and 10 species with “heron” common names, including the great blue heron (Ardea herodias). There’s no significant biological boundary between herons and egrets; perhaps it’s easiest to think of it this way – “egret” is the common name generally assigned to the whiter herons.

Great egrets are found near water, whether fresh or salt, and most closely associated with wetlands. During the breeding season, they get all gussied up. Each egret, both males and females, grow long plumes called aigrettes (from the French for “egret”), which cascade down its back. The egret’s unfeathered parts also become more intensely colored; the flesh around the eyes and between the eyes and bill turns emerald and pistachio, and the bill itself becomes more saturated carrot and saffron. The aforementioned aigrettes help egrets attract a mate, but they also caught the eye of late-19th century Europeans, who desired the plumes for ladies’ hats. As a result, great egrets were one of a number of “white heron” species that were exploited and over-hunted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 1880s, demand was so high that the plumes sold for twice the price of gold! Fortunately, some hunter-conservationists of the day noticed that populations of waterbirds were reeling from the combination of habitat loss and the myopic, kill-them-all-for-today’s-pay-day approach of market hunters, and they resolved to take action. The reforms they managed to pass represent major victories for the then-nascent conservation movement and, importantly, allowed many waterbird and shorebird populations to recover.

This color column is based on A. a. egretta, the subspecies that occurs in the Americas.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.