Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

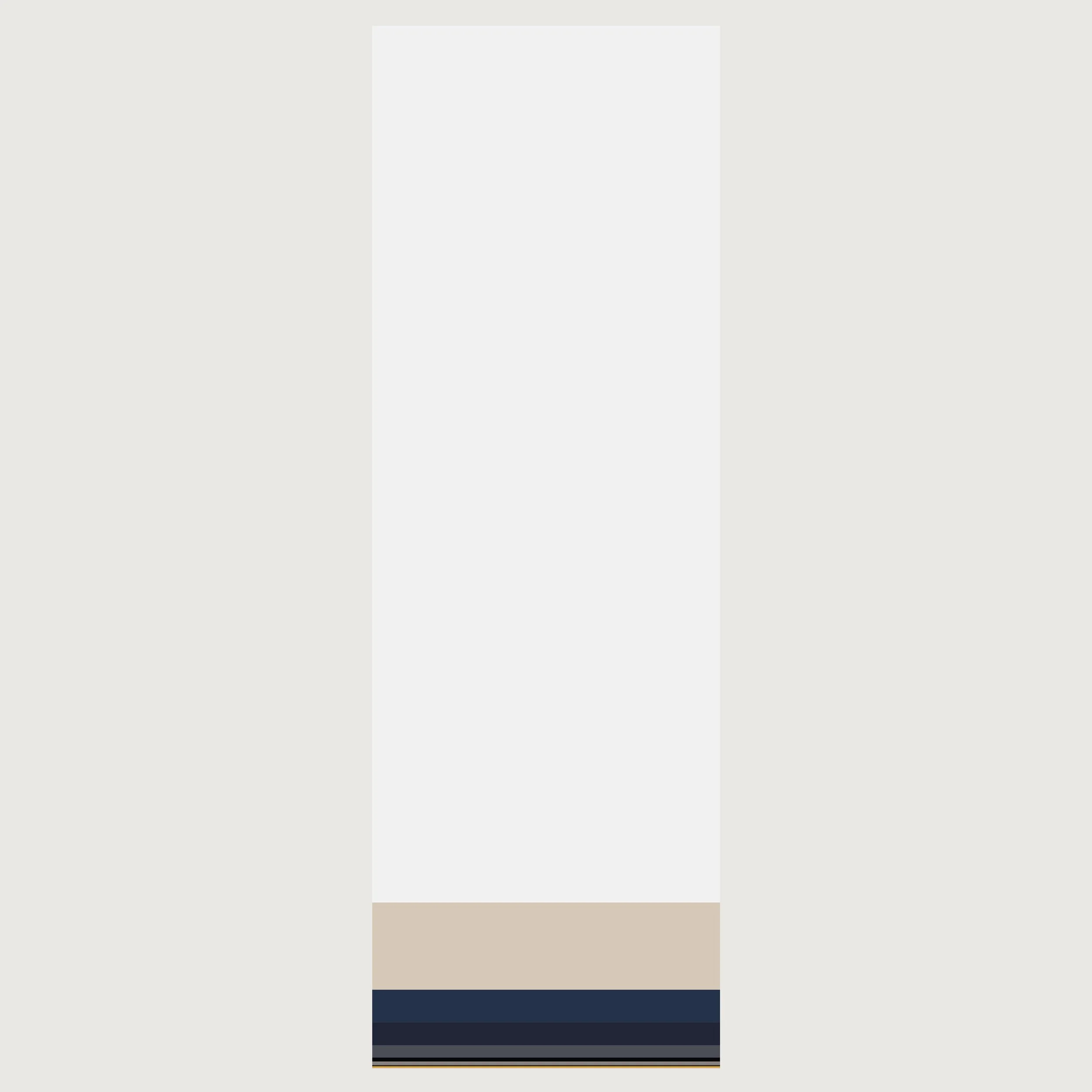

Image 2 of 3

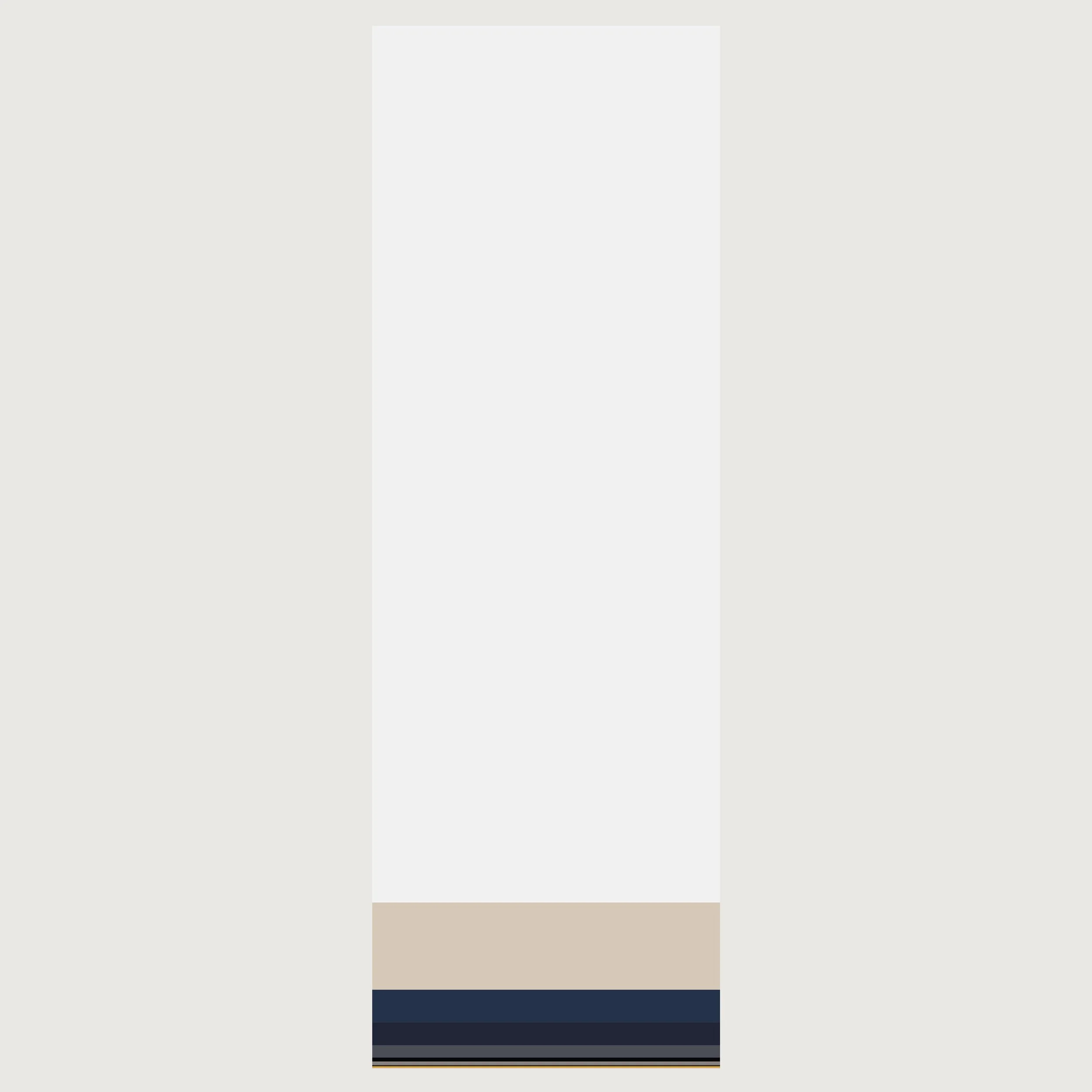

Image 2 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

Field Guide : Tundra Swan

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The tundra swan is one of two swan species native to North America. Its common name is apt; it breeds in the arctic and subarctic reaches of North America and Asia – in other words, on the tundra. Like most sexually monomorphic birds (species in which both sexes look the same), tundra swans mate for life. The pairs arrive on their northern breeding grounds in March and April. It’s there, on the tundra, that they face most of their natural predators; foxes, eagles, jaegers and gulls, ravens, weasels, and even bears target the nests, as the swan eggs make for excellent food. Even adult swans occasionally fall prey to eagles, wolves, and bears.

Humanity, though, plays the greatest role when it comes to tundra swan mortality and conservation challenges. Hunting and poaching, water pollution, and habitat degradation are all concerns today. Tundra swan hunting is strictly managed in the states that allow it, but some biologists believe the bag limits are too lenient. Beyond that legal “take,” poaching remains a problem, and tundra swans are regularly targeted by native subsistence hunters, as well. It is estimated that ~4,000 tundra swans are legally killed by licensed North American hunters each year, with an additional ~6,000–10,000 killed by poachers and subsistence hunters. Still, the tundra swan population has remained stable in the face of hunting, poaching, and environmental pressures. Perhaps the greatest threat – and one receiving relatively little attention – is the range expansion of the invasive mute swan.

The mute swan is the swan you probably know well from European folk and fairy tales, ballets, and Disney movies. Here, in North America, though, where it was first introduced in the early 20th century, it’s an ugly (duckling) problem. Mute swans are much larger and more aggressive than tundra swans; they’re also non-migratory, meaning they stay year-round on the habitat that the tundra swans return to each winter. The mute swans feed heavily and, in so doing, greatly reduce the amount of food available for their migratory cousins. Moreover, unlike tundra swans, mute swans seem to thrive in degraded habitats and they do very well living immediately alongside humans, to boot.

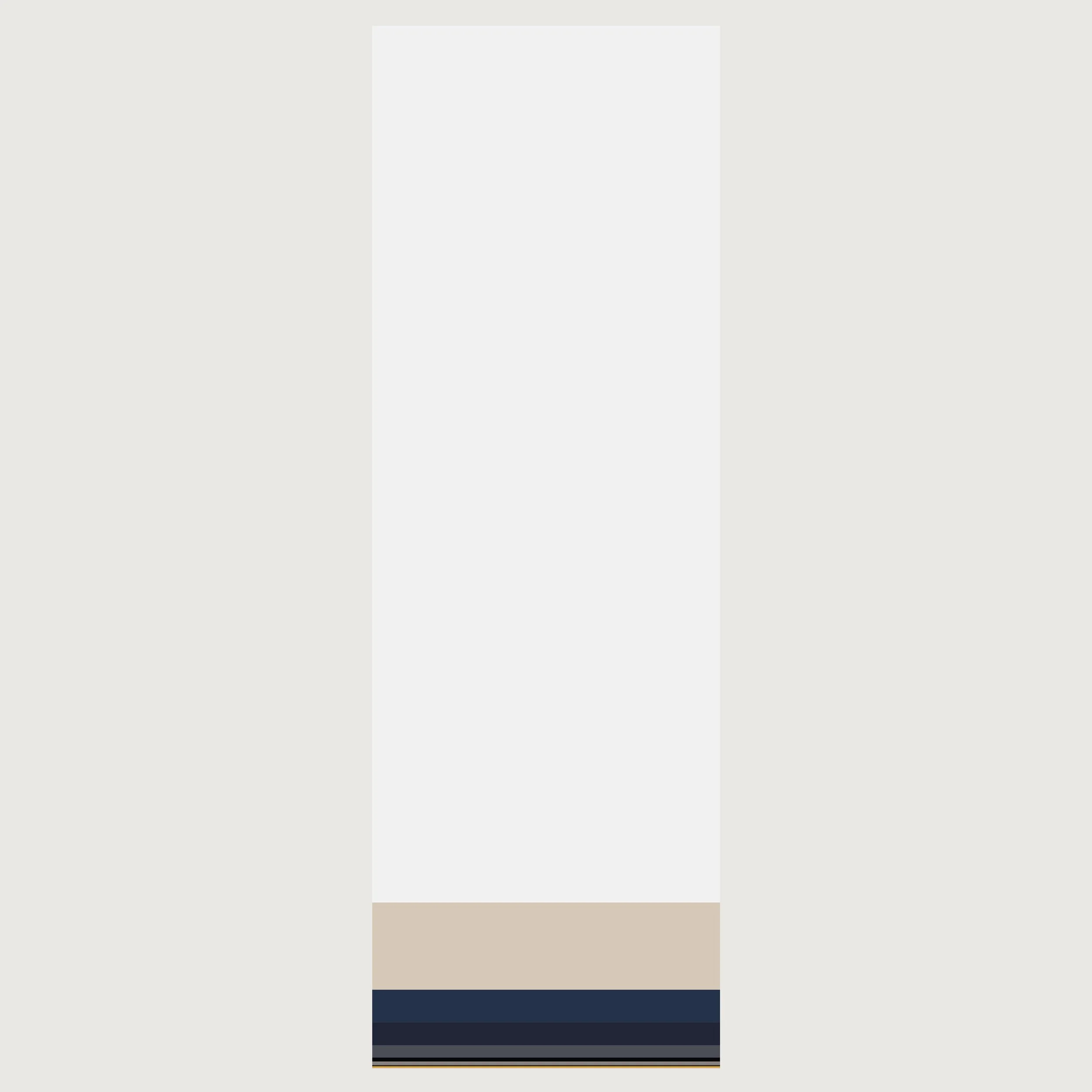

There are two subspecies of tundra swan. The North American subspecies, sometimes called the whistling swan (Cygnus columbianus columbianus), is the model for this color column. The European subspecies, also known as Bewick’s swan (Cygnus columbianus bewickii), shows more yellow on the bill’s lore, averages slightly smaller than its North American kin, and can be found breeding across the Siberian arctic and wintering in western Europe, near the Caspian Sea, eastern China, Korea, and Japan.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.

Unlimited edition. 18 x 24 inch, museum-quality poster on matte paper.

The tundra swan is one of two swan species native to North America. Its common name is apt; it breeds in the arctic and subarctic reaches of North America and Asia – in other words, on the tundra. Like most sexually monomorphic birds (species in which both sexes look the same), tundra swans mate for life. The pairs arrive on their northern breeding grounds in March and April. It’s there, on the tundra, that they face most of their natural predators; foxes, eagles, jaegers and gulls, ravens, weasels, and even bears target the nests, as the swan eggs make for excellent food. Even adult swans occasionally fall prey to eagles, wolves, and bears.

Humanity, though, plays the greatest role when it comes to tundra swan mortality and conservation challenges. Hunting and poaching, water pollution, and habitat degradation are all concerns today. Tundra swan hunting is strictly managed in the states that allow it, but some biologists believe the bag limits are too lenient. Beyond that legal “take,” poaching remains a problem, and tundra swans are regularly targeted by native subsistence hunters, as well. It is estimated that ~4,000 tundra swans are legally killed by licensed North American hunters each year, with an additional ~6,000–10,000 killed by poachers and subsistence hunters. Still, the tundra swan population has remained stable in the face of hunting, poaching, and environmental pressures. Perhaps the greatest threat – and one receiving relatively little attention – is the range expansion of the invasive mute swan.

The mute swan is the swan you probably know well from European folk and fairy tales, ballets, and Disney movies. Here, in North America, though, where it was first introduced in the early 20th century, it’s an ugly (duckling) problem. Mute swans are much larger and more aggressive than tundra swans; they’re also non-migratory, meaning they stay year-round on the habitat that the tundra swans return to each winter. The mute swans feed heavily and, in so doing, greatly reduce the amount of food available for their migratory cousins. Moreover, unlike tundra swans, mute swans seem to thrive in degraded habitats and they do very well living immediately alongside humans, to boot.

There are two subspecies of tundra swan. The North American subspecies, sometimes called the whistling swan (Cygnus columbianus columbianus), is the model for this color column. The European subspecies, also known as Bewick’s swan (Cygnus columbianus bewickii), shows more yellow on the bill’s lore, averages slightly smaller than its North American kin, and can be found breeding across the Siberian arctic and wintering in western Europe, near the Caspian Sea, eastern China, Korea, and Japan.

Note: These archival poster prints feature rich, appealing colors. I encourage customers to take care in handling them until they are framed/protected for display; the darker colors on the matte paper can be scratched. They ship rolled, so customers need to flatten them before framing (or have their framer do so).

Charitable Sales Model: Whenever one of these poster prints is purchased, a charitable contribution equal to 10% of the print’s cost (or $3.60) is made to a nonprofit working to tackle environmental or social challenges. Read more about my charitable sales model here.